This is the book notes of The Time-Crunched Cyclist: Race-Winning Fitness in 6 Hours a Week, 3rd Ed. (The Time-Crunched Athlete). I find it very useful.

Science behind Cycling Performance

Your performance depends on developing three fundamental energy systems. These energy systems power all activities, and the goal of performance training is to get all three working at optimum levels. The systems are:

- Immediate energy, which involves the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and creatine phosphate (CP) systems

- Aerobic system, which is the body’s preferred energy system

- Glycolytic system, which the body uses to meet the demands of relatively short, high intensity efforts

For an endurance athlete, the primary goal of training is to increase the amount of oxygen your body can absorb, deliver, and process. One of the biggest keys to building this oxygen-processing capacity is increasing mitochondrial density, or the size and number of mitochondria in muscle cells.

Glycolysis — to put it in its simplest terms — rapidly delivers the ATP necessary to meet your increased energy demand by converting glucose (sugar) into lactate in order to keep other energy-producing reactions moving.

The faster you can process lactate, the more work you can perform before lactate levels in your muscles and blood start to rise, and the faster you can recover from hard efforts. Lactate threshold is the point at which your demand for energy outstrips the aerobic system’s ability to deliver it, but lactate threshold doesn’t define the maximum amount of oxygen your body can use. When your exercise intensity reaches its absolute peak, and your body is pulling in and using as much oxygen as it possibly can, you’re at VO2max. This is your maximum aerobic capacity, and it is one of the most important indicators of your potential as an endurance athlete.

High-intensity training has been extensively studied, and the basic premise of a training program that utilizes intervals at and near an athlete’s VO2max is that efforts at this intensity level lead to many of the same physiological adaptations that result from more traditional endurance training models. In high-intensity training programs, the recovery times between intervals are just as important as what’s referred to as the “work time.”

When you distill the world’s most successful training programs, across all sports, you arrive at five distinct principles of training:

- Overload and recovery: The human body is designed to respond to overload, and as long as you overload a system in the body properly and allow it time to adapt, that system will grow stronger and be ready for the same stress in the future. To achieve positive training effects, this principle must be applied to individual training sessions as well as to entire periods of your training. Gains are made when you allow enough time for your body to recover and adapt to the stresses you have applied.

- Individuality

- Specificity

- Progression: Time and intensity are the two most significant variables you can use to adjust your workload. You can use the two variables of time and intensity to manipulate training a hundred different ways, but the end result must be that you’re generating a training stimulus great enough to make your muscles and aerobic engine adapt.

- Systematic approach: A successful training program must be well thought out and organized so your body advances through a planned series of training and recovery periods.

Training workload is the product of volume and intensity, but compared with the effect of increasing volume, increasing intensity results in an exponential increase in workload. As a result, high-intensity training programs can generate great workloads despite very low training volumes.

you can use the following five variables to address the five principles of training discussed in the previous section:

- Intensity

- Volume

- Frequency and repetition: Frequency is the number of times a workout is performed in a given period of training, whereas repetition is the number of times an exercise is repeated in a single session.

- Terrain

- Cadence: You can produce 250 watts at 80 rpm or 100 rpm, but your leg muscles will fatigue faster riding a bigger gear at 80 rpm than a lower gear at 100 rpm, even though the power output (wattage) is the same. Maintaining higher cadences helps shift stress from easily fatigued skeletal muscles to the fatigue-resistant cardiovascular system.

Climbing at a cadence of 70 revolutions per minute (rpm) will tend to push an athlete to his or her climbing lactate threshold, which is slightly higher than the flat-ground lactate threshold due to an increase in muscle recruitment. I prescribe such workouts to develop an athlete’s ability to sustain prolonged climbing efforts in races. But if the same climbing workout is done at a cadence of 50 rpm, the tension applied to the leg muscles increases greatly, and the stress on the cardiovascular system decreases.

Improvement in training can be measured by whether you can produce more power at the same relative effort level as before and/or whether you can sustain that power output longer than you could before. iIcreasing sustainable power at lactate threshold and increasing power at VO2max are the best ways to improve cycling performance. In addition, it’s important not only to focus on achieving higher wattages at these levels but also to work on increasing the amount of time you can sustain those intensities.

A cyclist’s efficiency is about 20 to 25 percent, meaning that about 75 to 80 percent of the energy you expend is lost, mostly as heat. You can generally consider the number of kilojoules displayed on your power meter to be equal to the number of kilocalories you burned during your time on the bike. While kilojoules provide raw information about the endurance component of your training, this information must be considered in conjunction with time and intensity. That is, you need to think about how you produced those kilojoules to evaluate the ride’s impact on your fitness, performance, and fatigue. The inverse relationship between power output and exercise duration also means that relatively short training sessions can prepare you for longer events. As you build a bigger aerobic engine, you’re gaining the fitness necessary to produce more kilojoules per hour through primarily aerobic metabolism.

CTS Field Test

The CTS Field Test consists of two 8-minute, all-out time trials separated by 10 minutes of easy spinning recovery. The CTS Field Test generates average power outputs that are about 10 percent above an athlete’s lab-tested lactate threshold power output.

The higest CTS Field Test average is used as the baseline for all the workouts below. Using 180w as the CTS power.

Workouts

Two of the most effective cycling workouts are Tempo and Steady State. Tempo is a moderate-intensity aerobic interval that lasts 20–60 minutes. You just pedal steadily in a somewhat heavy gear (to keep you cadence relatively low) at a power output a little above your cruising pace and well below your lactate threshold. SteadyStates are 6- to 20-minute intervals near your lactate threshold power output, separated by easy spinning recovery periods half the duration of the intervals.

Fast Pedal (FP)

This workout should be performed on a relatively flat section of road. The gearing should be light, with low pedal resistance. Begin slowly working up your pedal speed, starting out with around 15 to 16 pedal revolutions per 10-second count. This equates to a cadence of 90 to 96 rpm. While staying in the saddle, increase your pedal speed, keeping your hips smooth, with no rocking. Concentrate on pulling through the bottom of the pedal stroke and pushing over the top. After 1 minute of FP you should be maintaining 18 to 20 pedal revolutions per 10-second count, or a cadence of 108 to 120 rpm for the entire time prescribed for the workout. Your heart rate (HR) will climb while doing this workout, but don’t use it to judge your training intensity. It is important that you try to ride the entire length of the FP workout with as few interruptions as possible, because it should consist of consecutive riding at the prescribed training intensity.

Endurance Miles (EM)

- HR: 50-91%

- Power: 45-73%, or 81-131w

- Cadence: 85-95

This is your moderate-paced endurance intensity. The point is to stay at an intensity below lactate threshold for the vast majority of any time you’re riding at EM pace. The heart rate and power ranges for this intensity are very wide to allow for varying conditions. It is OK for your power to dip on descents or in tailwinds, just as it is expected that your power will increase when you climb small hills. One mistake some riders make is to stay at the high end of their EM range for their entire ride. As you’ll see from the intensity ranges for Tempo workouts, the upper end of EM overlaps with Tempo. If you constantly ride in your Tempo range instead of using that as a distinct interval intensity, you may not have the power to complete high-quality intervals when the time comes. You’re better off keeping your power and/or heart rate in the middle portion of your EM range and allowing it to fluctuate up and down from there as the terrain and wind dictate. Use your gearing as you hit the hills to remain in the saddle as you climb. Expect to keep your pedal speed up into the 85 to 95 rpm range.

Tempo (T)

- HR: 88-90%

- Power: 80-85%, or 144-153w

- Cadence: 70-75

Tempo is an excellent workout for developing aerobic power and endurance. The intensity is well below lactate threshold, but it’s hard enough that you are generating a significant amount of lactate and forcing your body to buffer and process it. The intervals are long (15 minutes minimum, and they can be as long as 2 hours for pros), and your gearing should be relatively large so that your cadence comes down to about 70 to 75 rpm. This combination helps increase pedal resistance and strengthens leg muscles. Also, try to stay in the saddle when you hit hills during your T workouts. It is important that you try to ride the entire length of the T workout with as few interruptions as possible—T workouts should consist of consecutive riding at the prescribed intensity to achieve maximum benefit.

Steady State (SS)

- HR: 92-94%

- Power: 86-90%, or 154-162w

- Cadence: 85-95

These intervals are great for increasing a cyclist’s maximum sustainable power because the intensity is below lactate threshold but close to it. As you accumulate time at this intensity, you are forcing your body to deal with a lot of lactate for a relatively prolonged period of time. SS intervals are best performed on flat roads or small rolling hills. If you end up doing them on a sustained climb, you should really bump the intensity up to ClimbingRepeat range, which reflects the grade’s added contribution to your effort. Do your best to complete these intervals without interruptions from stoplights and so on, and maintain a cadence of 85 to 95 rpm. Maintaining the training zone intensity is the most important factor, not pedal cadence. SS intervals are meant to be slightly below your individual time trial pace, so don’t make the mistake of riding at time trial pace during them. Recovery time between SS intervals is typically about half the length of the interval itself.

Climbing Repeats (CR)

- HR: 95-97%

- Power: 95-100%, or 171-180w

- Cadence: 70-85

This workout should be performed on a road with a long steady climb. The training intensity is designed to be similar to that of a SS interval but reflect the additional workload necessary to ride uphill. The intensity is just below your lactate threshold power and/or heart rate, and it is critical that you maintain this intensity for the length of the CR. Pedal cadence for CR intervals while climbing should be 70 to 85 rpm. Maintaining the training intensity is the most important factor, not pedal cadence. It is very important to avoid interruptions while doing these intervals. Recovery time between intervals is typically about half the length of the interval itself. This interval is not used as a stand-alone training intensity in the TCTP, but it is used as a component of the OverUnder intervals.

Power Intervals (PI)

- HR: 100% max

- Power: 101%, or more than 180w

- Cadence: 100+

PowerIntervals are perhaps the most important workouts in the entire TCTP. These short efforts are the way you’re going to apply the concepts of high-intensity training to your program to make big aerobic gains in a small amount of time. These intervals are maximal efforts and can be performed on any terrain except sustained descents. Your gearing should be moderate so you can maintain a relatively high pedal cadence (100 rpm or higher is best).

Steady Effort Power Intervals (SEPI)

Try to reach and maintain as high a power output as possible for the duration of these intervals. Ideally, these efforts should look like flat plateaus when you view your power files. Take the first 30 to 45 seconds to gradually bring your power up and then hold on for the rest of the interval. The point here is to accumulate as much time as possible at a relatively constant and extremely high output.

Peak-and-Fade Power Intervals (PFPI)

These intervals start with a big acceleration rather than a gradual increase in intensity. Go all-out right from the beginning and keep your power output as high as possible as the interval progresses. Because of the hard acceleration, your power output will fall after the first 40 to 60 seconds. That’s expected and perfectly normal; just keep pushing. Keep a high cadence (above 90 rpm) for the entire interval. Don’t let fatigue lead you to start mashing gears in the second half of the effort.

Over-Under (OU) Intervals

OverUnder intervals are a more advanced form of SS intervals. The “Under” intensity is your SS range, and the “Over” intensity is your CR range. By alternating between these two intensity levels during a sustained interval, you develop the “agility” to handle changes in pace during hard sustained efforts. More specifically, the harder surges within the interval generate more lactate in your muscles, and then you force your body to process this lactate while you’re still riding at a relatively high intensity.

To complete the interval, bring your intensity up to your SS range during the first 45 to 60 seconds. Maintain this heart rate intensity for the prescribed Under time and then increase your intensity to your Over intensity for the prescribed time. At the end of this Over time, return to your Under intensity range and continue riding at this level of effort until it’s once again time to return to your Over intensity. Continue alternating this way until the end of the interval.

Note: In the training programs, the parameters of the OU intervals are written as 3 × 12 OU (2U, 1O), 5 minutes RBI. This should be read as follows: Three intervals of 12 minutes. During the 12-minute intervals, the first 2 minutes should be at your Under intensity (2U). After 2 minutes, accelerate to your Over intensity for 1 minute (1O), before returning to your Under intensity for another 2 minutes. Continue alternating in this manner—in this example you’d complete 4 cycles of Under and Over—until the end of the interval. Spin easy for 5 minutes and start the next interval.

Threshold Ladders (TL)

ThresholdLadders mimic the accelerations and sustained power requirements used in breakaways, the start of races, and anytime you need to accelerate hard and then gradually settle into a sustainable pace. They begin with a 1- to 2-minute all-out PowerInterval, followed immediately by 3 to 4 minutes at ClimbingRepeat intensity (95–100 percent of threshold power), and end with 5 to 6 minutes at SteadyState power (86–90 percent of power at threshold).

Training Programs

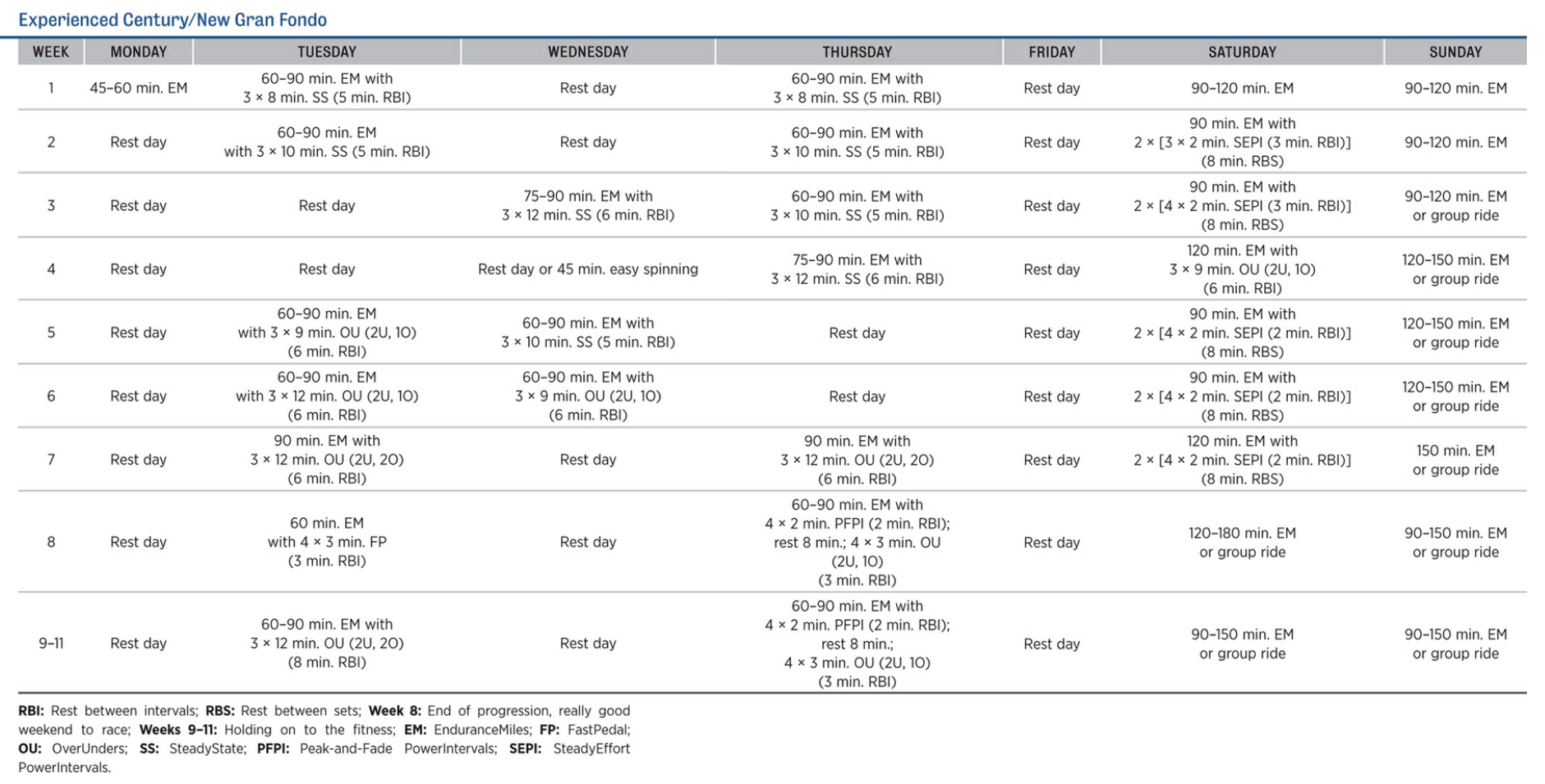

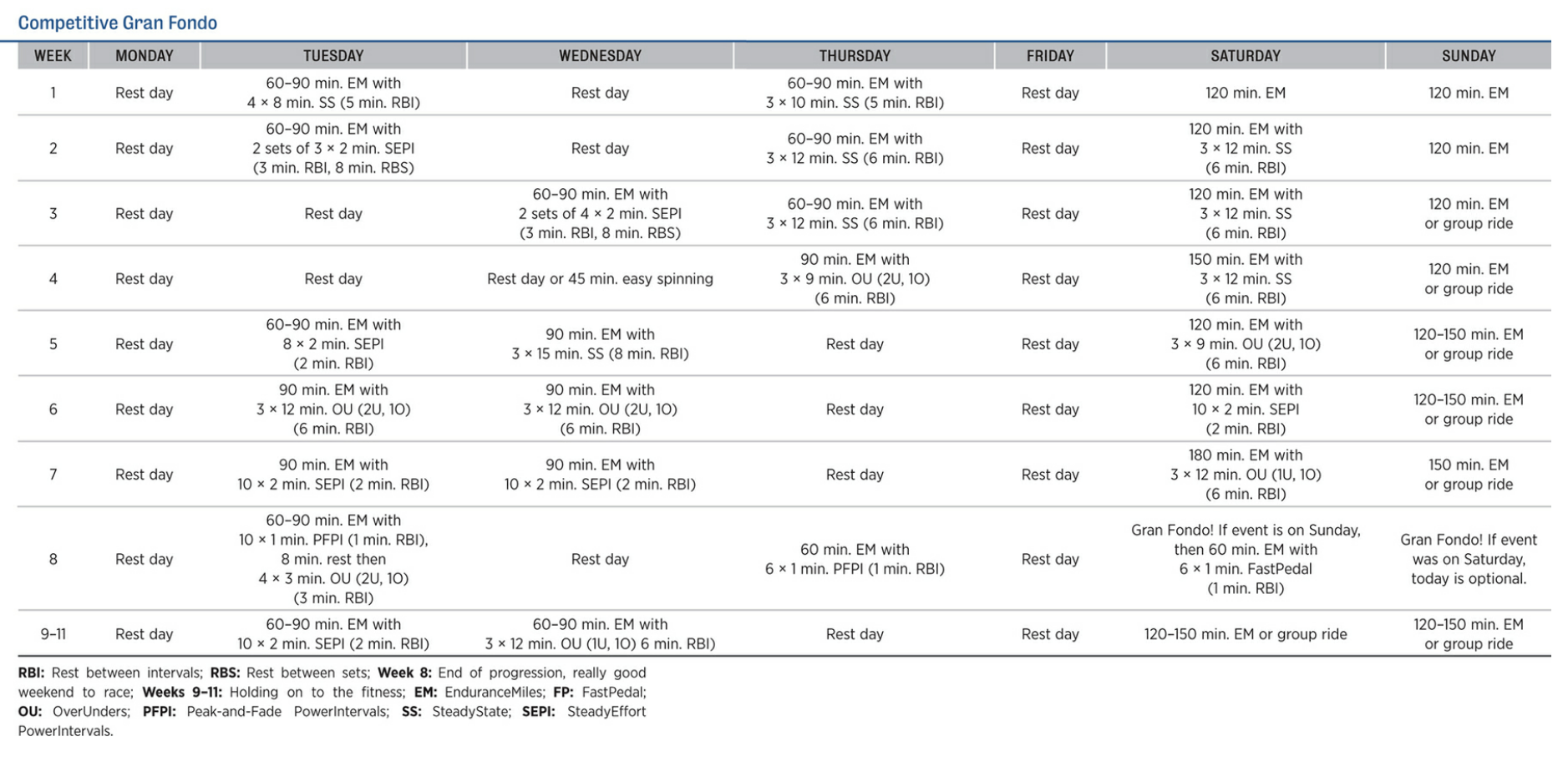

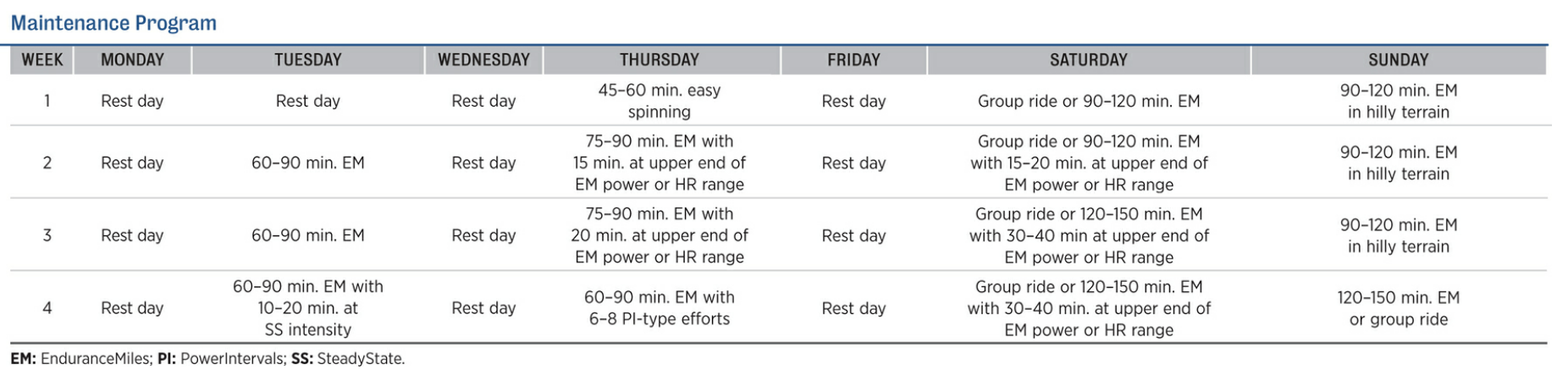

CTS training programs are usually 11 weeks long, with peak performance reached at the end of week 8. Week 9-11 is to keep the performance at peak. After 11 weeks, you should take 6 weeks off before starting another one. You can use the maintenance program during the 6-week off time.

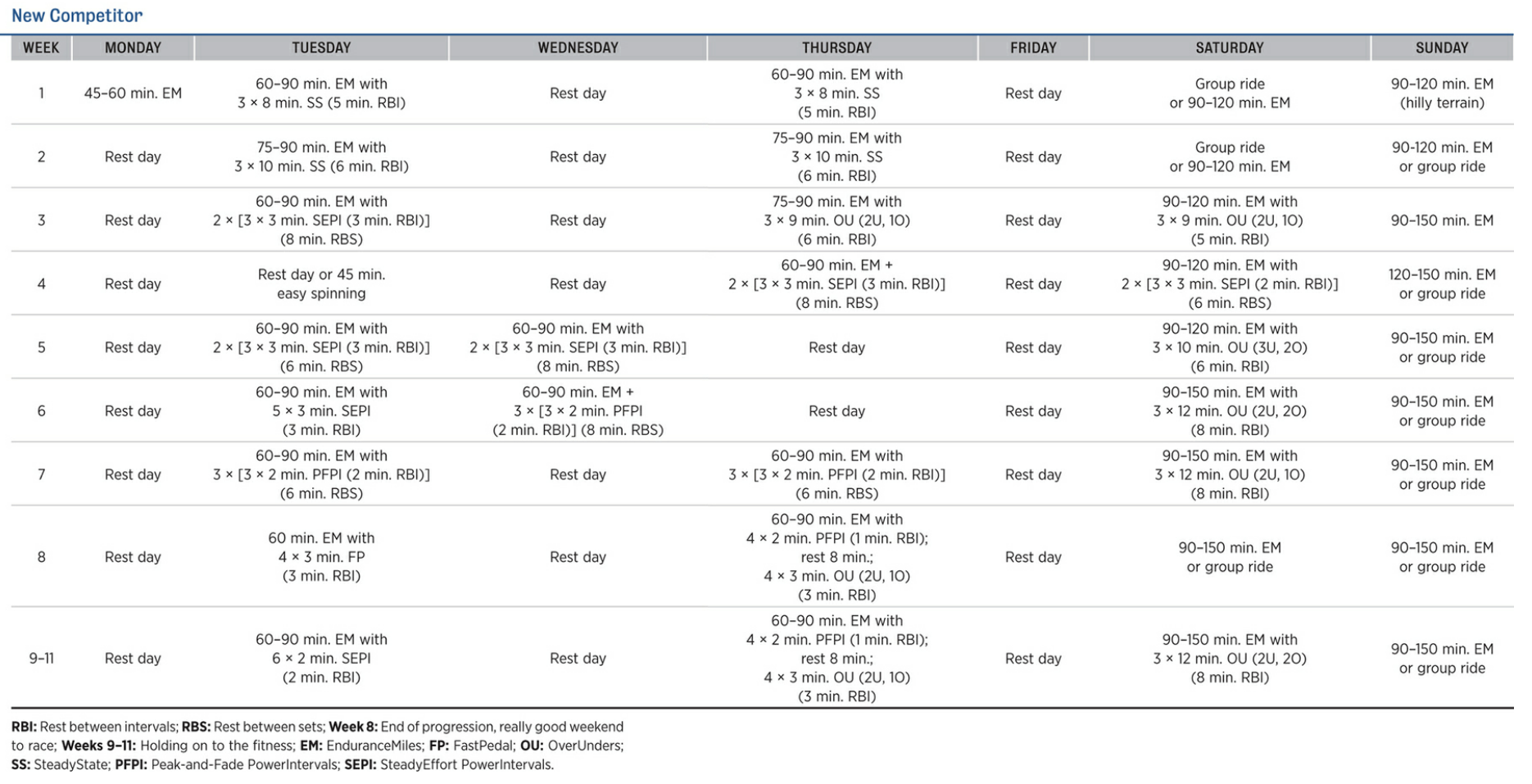

Road Race - New Competitor

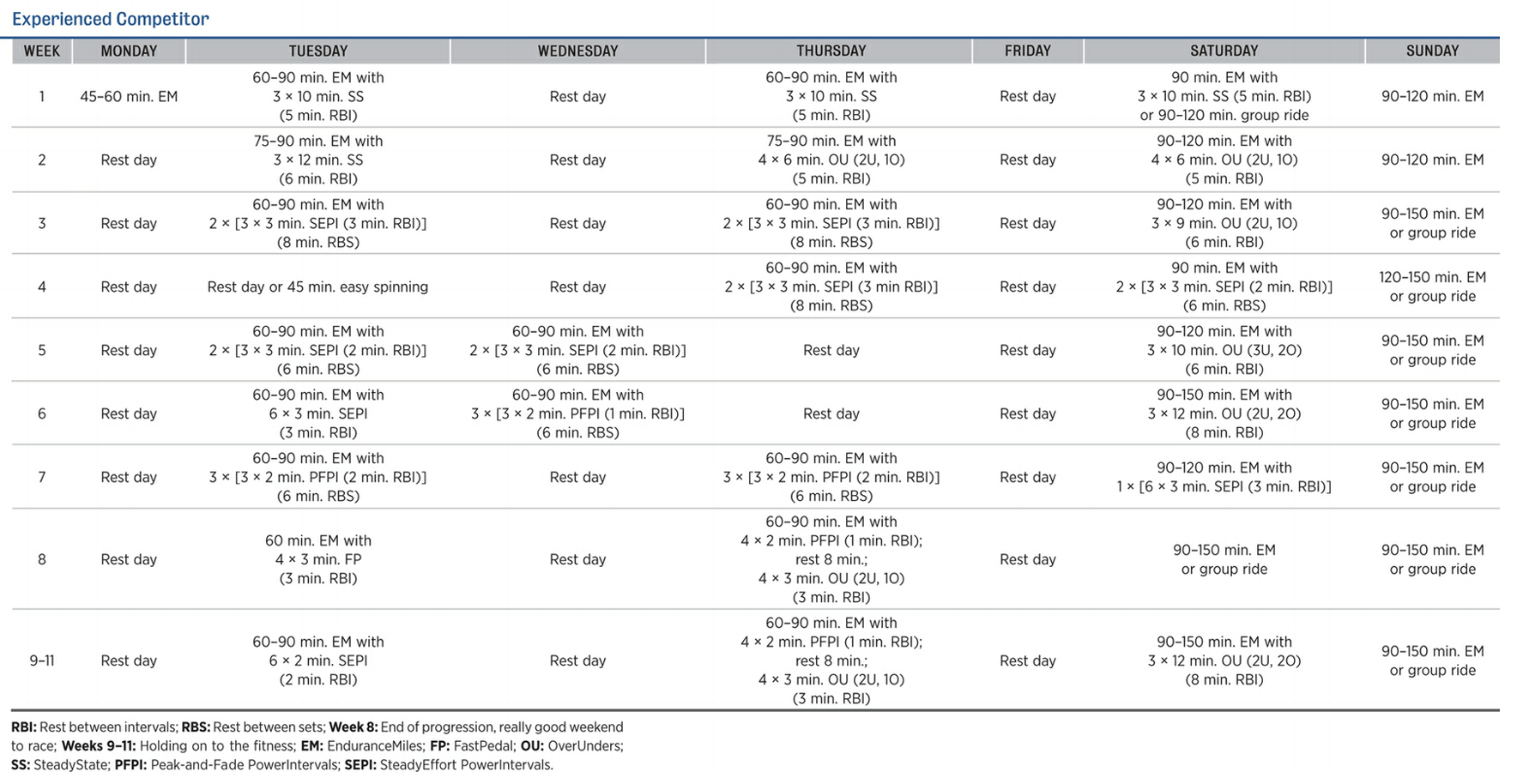

Road Race - Experienced Competitor

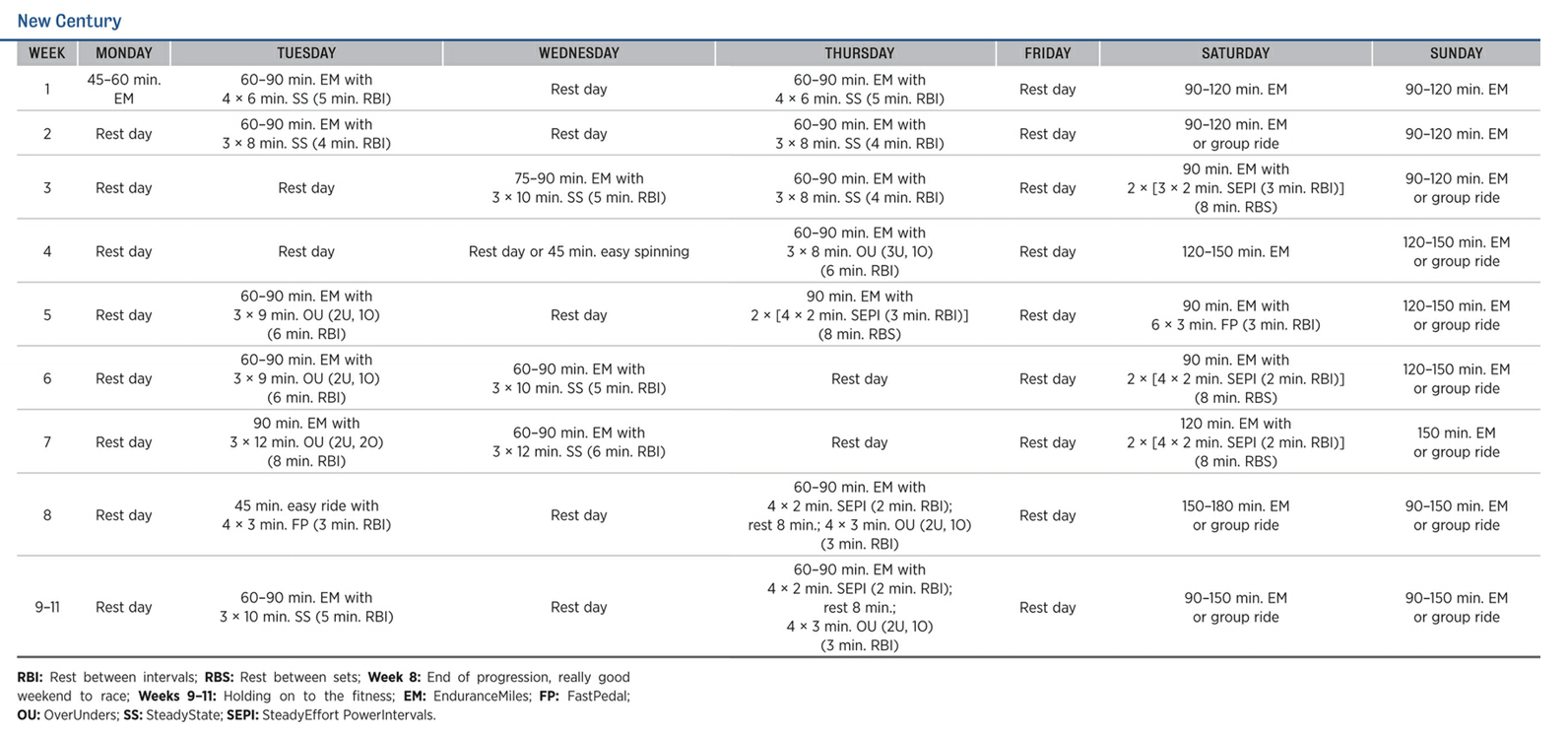

Endurance - Entry Level

Endurance - Intermediate Level

Endurance - Advanced Level

Maintenance Program

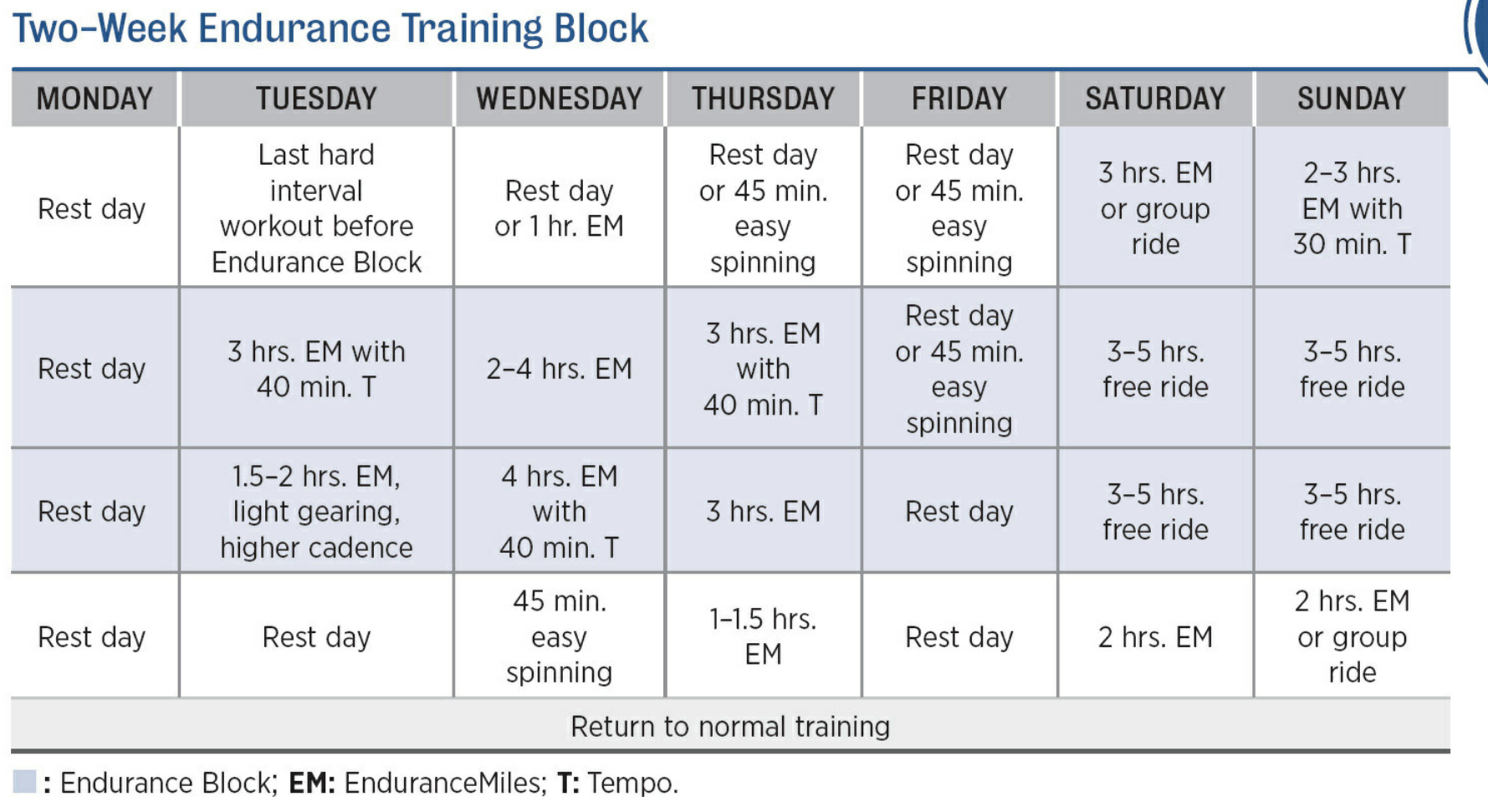

Endurance - Training Block

This program is used when you find more time to ride your bikes.